“Consciousness,” in the Buddhist context, is a translation of vijnana, a Sanskrit word meaning “perception.” It refers not only to waking awareness but also to internal capacities and energies that direct our lives.

The first five levels of consciousness correspond to our five sensory organs—eyes, ears, nose, tongue and skin.

They are: 1) sight- consciousness, 2) hearing-consciousness, 3) smell-consciousness, 4) taste-consciousness and 5) touch-consciousness.

These gather and perceive information about the world and pass it to the sixth consciousness, the ‘mind-consciousness’, which integrates the information into coherent images, assesses it and forms responses. Suppose someone is yelling at you. You perceive this information through your five senses, and your sixth consciousness interprets it, con- cludes the person is angry and considers and initiates a response.

The sixth consciousness is always at work in support of our day-to-day activities.

Memory, imagination and dreams also take place on this level, so the mind-consciousness can be at work even without immediate input from the five senses.

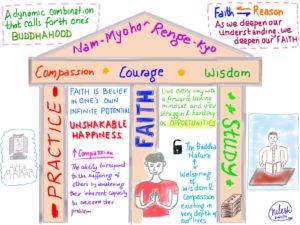

These first six levels are strongly influenced by deeper levels of consciousness. Impulses arising from the seventh and eighth levels of consciousness affect the way the five senses perceive information and how the mind interprets it. Emotions, deep-seated attitudes and self-attachment can change or skew our perception. By purifying the first six levels of consciousness, we are able to perceive all things in their true light. This is why Nichiren describes “purification of the six sense organs” as an important benefit of Buddhist practice.

Unlike the first six levels, the seventh,‘manas– consciousness’, does not depend directly on the external world. It is the internal, spiritual, intuitive realm of life where self-attachment and the ability to distinguish oneself from others, capacities necessary for survival, reside. This subconscious drive to differentiate self from others, however, if too strong, gives rise to arrogance, insecurity, conflict and misery. So while the sixth consciousness enables you to decide that your friend is angry, the seventh determines how that makes you feel and how it affects your sense of identity. If that sense is unbalanced, this might lead you to act in a way that compounds the problem. The seventh level also includes one’s sense of right and wrong, which if healthy can overpower the impulse to act selfishly or rashly.

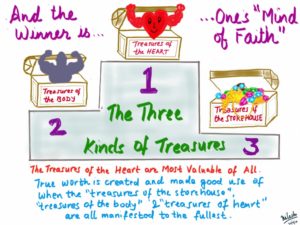

The eighth level is the alaya-consciousness— the Sanskrit word alaya meaning “storehouse.” It is the “karmic storehouse” where latent causes and effects resulting from all one’s thoughts, words and deeds throughout time reside. Your reaction to your friend’s anger will be influenced by all your past causes and effects. The first seven levels of consciousness cease upon death, but the eighth persists eternally, carrying with it the distinct nature of one’s being throughout the cycle of birth and death.

SGI President Ikeda states: “The term storehouse conjures the image of an actual structure into which things of substance can be placed. But in fact it may be more accurate to say that the life current of kar- mic energy itself constitutes the eighth consciousness . . . Moreover, the eighth consciousness transcends the boundaries of the individual and interacts with the karmic energy of others. On the inner dimension of life, this latent karmic energy merges with the latent energy of one’s family, one’s ethnic group and humankind, and also with that of animals and plants” (The Wisdom of the Lotus Sutra, vol. 4, pp. 262–63).

This is why one person’s inner transformation, or “human revolution,” can change the destiny of a family, society and even of all humankind.

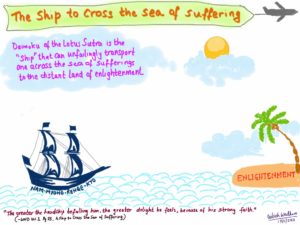

The traditional Buddhist view holds that changing negative karma for the better involves countering every past bad cause with a good cause. This process was thought to take countless lifetimes and require that no new bad causes be made—unlikely in a world filled with impure and negative influences.

In contrast, Nichiren taught that we can fundamentally transform our karma and create supreme value and happiness in this life by tapping into an even deeper, more powerful level of consciousness. This is the ninth consciousness, also called the ‘amala– consciousnes’—the Sanskrit word amala meaning “pure” or “stainless.” It is the “fundamental pure consciousness” existing at a depth of life free from all karmic impurity and is synonymous with the world of Buddhahood.

President Ikeda explains, “Just as the light of the stars and the moon seems to vanish when the sun rises, when we bring forth the state of Buddhahood in our lives we cease to suffer negative effects for each individual past offense committed” (August 2003 Living Bud- dhism, p. 47).

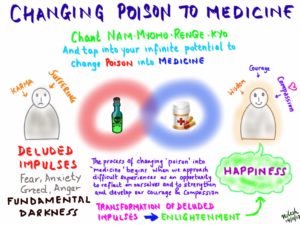

When we tap into our amala-consciousness by chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo, we can positively transform our karmic tendencies and reactions, and create value from every situation—even being yelled at by a friend. For instance, instead of taking offense, we can see the situation more clearly, perhaps even appreciating that person’s anger as a sign of concern.

Nichiren identifies the ninth consciousness as Nam-myoho-renge-kyo, which he embodied in the form of the Gohonzon. He teaches, “You should base your mind on the ninth consciousness, and carry out your practice in the six consciousnesses” (“Hell Is the Land of Tranquil Light,” The Writing of Nichiren Daishonin, vol. 1, p. 458). This means that those who practice Nichiren Buddhism reveal the qualities of a Buddha (the ninth consciousness) in their everyday behavior (the first six levels of consciousness).

Nichiren also states: “Never seek this Gohonzon outside yourself. The Gohon- zon exists only within the mortal flesh of us ordinary people who embrace the Lotus Sutra and chant Nam-myoho-renge-kyo. The body is the palace of the ninth consciousness, the unchanging reality that reigns over all of life’s functions” (“The Real Aspect of the Gohonzon,” WND-1, 832). Chanting Nam- myoho-renge-kyo to the Gohonzon with faith in our innate Buddha nature enables us to access this “palace of the ninth conscious- ness,” causing all other levels of consciousness to glow with the compassion, wisdom and courage of Buddhahood.

Source:http://www.sgi-usa.org/memberresources/study/2018_essentials_part3/docs/eng